The Dream Machine

an animated movie that had a 15 year launch pad

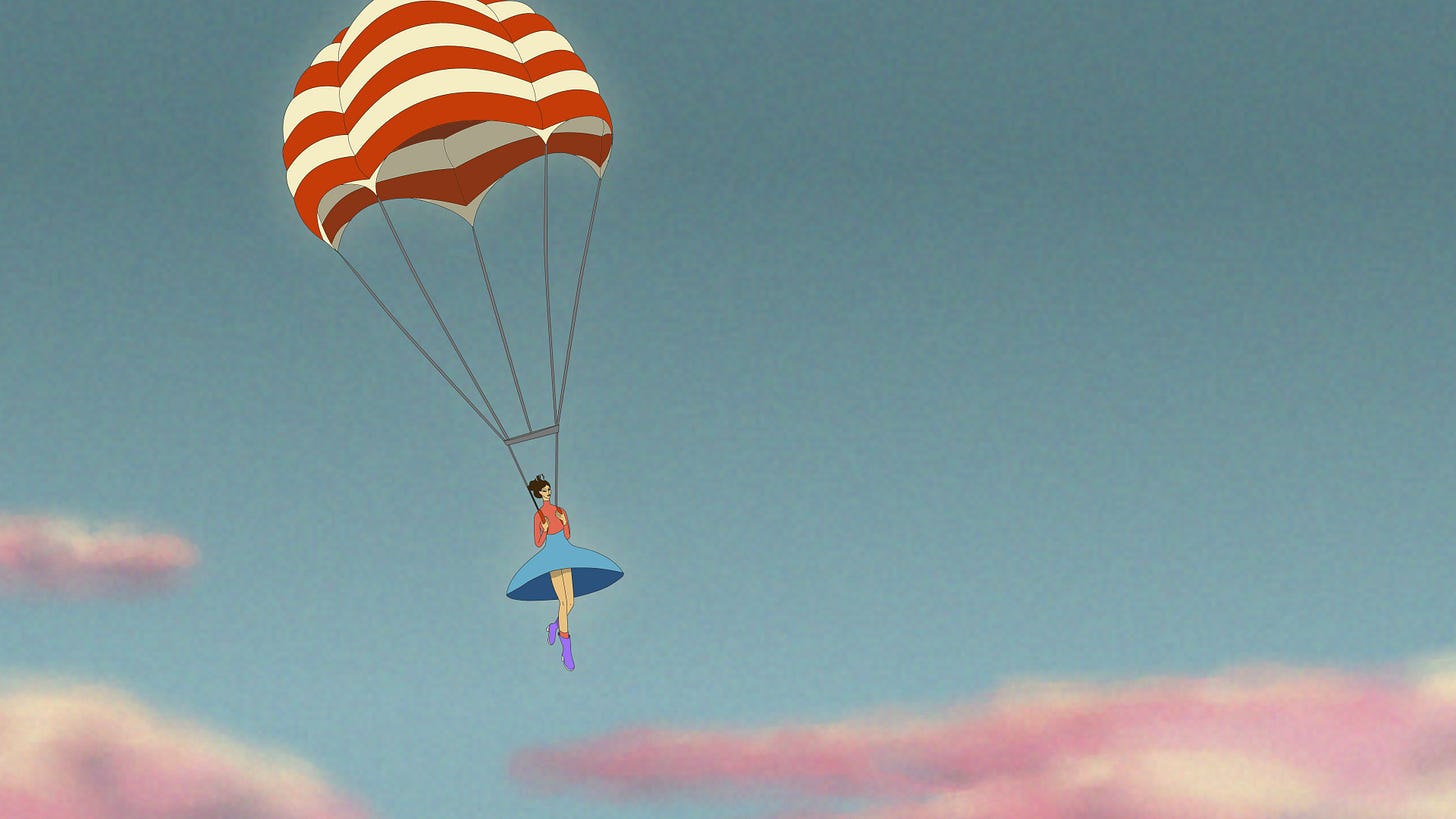

In March, 2025 I premiered a new short film I wrote and directed at SXSW called The Dream Machine.

Ahead of the festival, Indiewire said of it, “‘The Dream Machine’ is one of the highest-profile shorts playing SXSW 2025. Hailing from director Jimmy Marble and indie animator Francis Haszard, the creative exploration of grief is a reminder of the endless possibilities that come with short form filmmaking.”

The movie is about a woman who’s grieving the love of her life’s death, and her use of a novel invention that allows one to turn their dreams into reality by reading the atomic structure of their imagination and rebuilding it atom by atom. On the surface, I recognize that this reads very autobiographical. Oddly, however, this is a script I wrote when I was 22 years old, living in Paris, far away from marriage, quite well-versed in heartache, and deeply fascinated by the mysterious nature of the universe.

At the time I was 23 and developing my point of view on the aesthetics my art would showcase. Obama had just been sworn in a few months earlier, and the Bush years were still heavy on my mind as a young person. Namely, the media manipulation that led our country into multiple wars, the general public’s lack of literacy for visual culture, and their passive consumption of lies hidden by artifice. I was teaching a course on art history (survey of French New Wave, to be specific), and my job awarded me an orange ticket that allowed me into every museum in Paris for free. If I were meeting a friend for a beer, I’d see which museum was most near the cafe and get there a little early to just cruise in and see something beautiful on my way. As the year wore on, all I wanted was to spend time with Henri Matisse. I was in love with the modernist painters for all the inverse reasons I was so disappointed in American culture: The beauty was revealed through the honesty of artifice. The artifice was the whole story, not the hidden vessel of an idea or ideal. You loved it for the strokes, for the color harmony. The story and scene were low priorities. Propaganda would be impossible in this style, as the modern style requires you to think and enjoy the work critically, which is the opposite of what propaganda hopes for you.

I knew going forward I wanted my viewers to experience my work’s artifice first, the story second, in the hope that it would inspire the joy of critically engaging with the visual world around them.

I began writing scripts that would become my first short films with these goals in mind. (Also, this is another ‘stack for down the road, but at this point in my life I didn’t know how to take photos, had no interest in photography, and was only focused on being a director. Photography didn’t come to me until my late 20s. I believed photography was for dorks.)

By the time I left Paris in the summer of 2009, I had three scripts for three short films.

Cleo in the Universe: A space explorer gets an ultimatum from her longtime on-again off-again lover to meet her on the moon or lose her forever.

and

Red Moon: A loyal Soviet patriot/werewolf (an existence strictly forbidden by the communist party) becomes a submarine captain to hide from the cruel realities of his terrible secret.

and

The Dream Machine:

Cleo in the Universe and Red Moon are clear exercises on genre expectations. They were scripts I wanted to explore because of their aesthetics and rules I could break. But, The Dream Machine was a deeply romantic, philosophical piece that I craved to make because it was truly a piece of who I was. It was my creative heart exposed. I believed in them all, but I cared most about The Dream Machine.

I came to America radicalized and ready to make short films and change my life for the better. I had no money to spend, but I had friends and a strong sense that I could turn not having money into an aesthetic that could be beautiful.

In terms of movie-making, Cleo and Red Moon were relatively easy in that I was able to share the script, communicate the vision, translate it into sets and costumes, and get a large group of people all together at the same exact time. By 2011, both were finished, premiered, and my group of friends and I turned our attention to The Dream Machine.

But, the beginner’s luck ran out.

I had big ideas for making The Dream Machine in a sort of retro-futuristic Guy Maddin style that would infuse silent cinema styles with lush pastels. Art Deco meets Sgt. Peppers.

This was the first time I learned the reality of this goddamn biz: Making movies is hard. When my collaborators asked me, “So, how are we going to film this thing?” I didn’t have an answer because I couldn’t think of a good idea.

The film had a much more elaborate variety of locations, which necessitated a larger budget than I had ever had, especially if we wanted to stay committed to the hand-built aesthetic we had been creating. The furthest we got was screen testing my friend as Marianne, the short’s heroine.

It’s a little bit obscured in this photo’s crop, but Marianne’s styling was inspired by this gorgeously surreal photo of Greta Garbo with the USC track coach. This photo was my desktop background between ages 23-25. It feels like David Lynch to me. Bizarre and wonderful.

So, The Dream Machine was a dream deferred. Luckily, the first two short films were doing their job and somehow created a splash on the internet. Enough so that I began booking my first jobs as a director, and all of a sudden I was distracted enough to let this short film drift away from me as I began carving a career. The story was a nut I couldn’t crack. An aesthetic I couldn’t communicate. A missed opportunity.

The script kept collecting dust all the way until the dark days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when, for the first time since I had had a career, I all of a sudden didn’t. I was home and not on set, and I was getting itchy about it. A DP friend had been posting all these delightful animated sketches he had been making, and I was deeply inspired by them. Maybe, I thought, I should make an animated project.

I browsed all my old scripts to see if there were any I already had that might work as an animation. Lo and behold, my old flame, my first real love, The Dream Machine! When I re-read it, I was shocked that I ever thought it could be anything but animated. The way the universe collapses over and over again, and the way dreams move from one space to another in a blink: The whole project clicked into my brain in an instant. By the end of summer 2020, the movie was storyboarded.

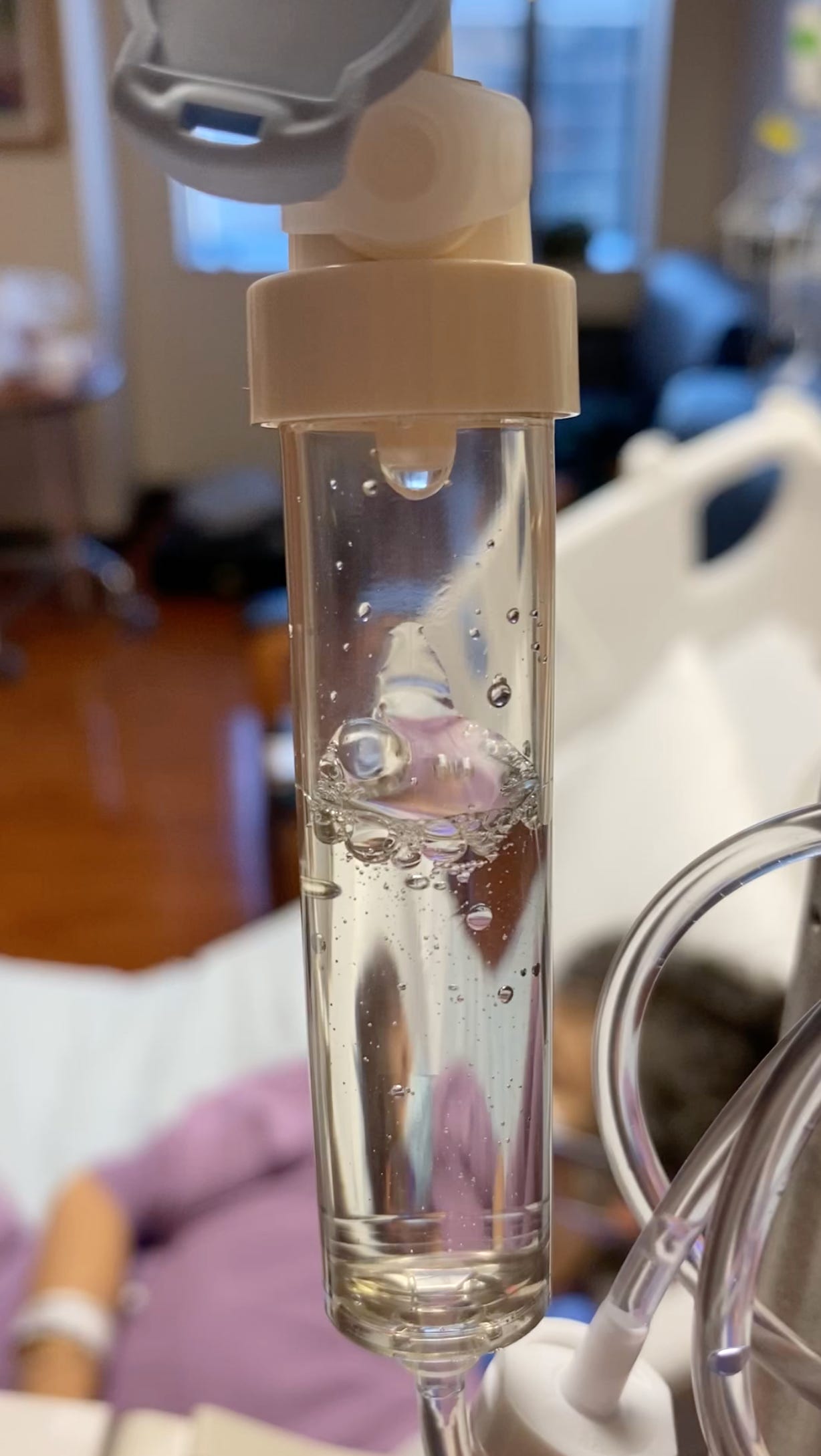

And by the end of fall 2020, my life fell apart. The painfully short version is my wife’s cancer relapsed after a secondary treatment and we were looking at either palliative care in California, or rolling the dice in Texas and trying for clinical trials at MD Anderson. By January we were living in Houston. By June we were back in Los Angeles, and I was saying goodbye to the woman I loved.

In the daze and shock of the loss, all I could do was find meaning in my work, and I began calling friends asking if they could help me with some temporary vocal tracks. Temp music. Rough sound effects. An edited animatic. By the end of the year it was a series of drawings you could watch like a short film. I shared it with the production company Ways & Means (my friends who have been producing many of my short films since 2015), and they got on board.

Sometimes the creative gods shine their most beautiful light on you, as was the case when I first met the animator Frances Haszard over Zoom in the spring of 2022. Her charm was disarming and her drawings were breathtaking.

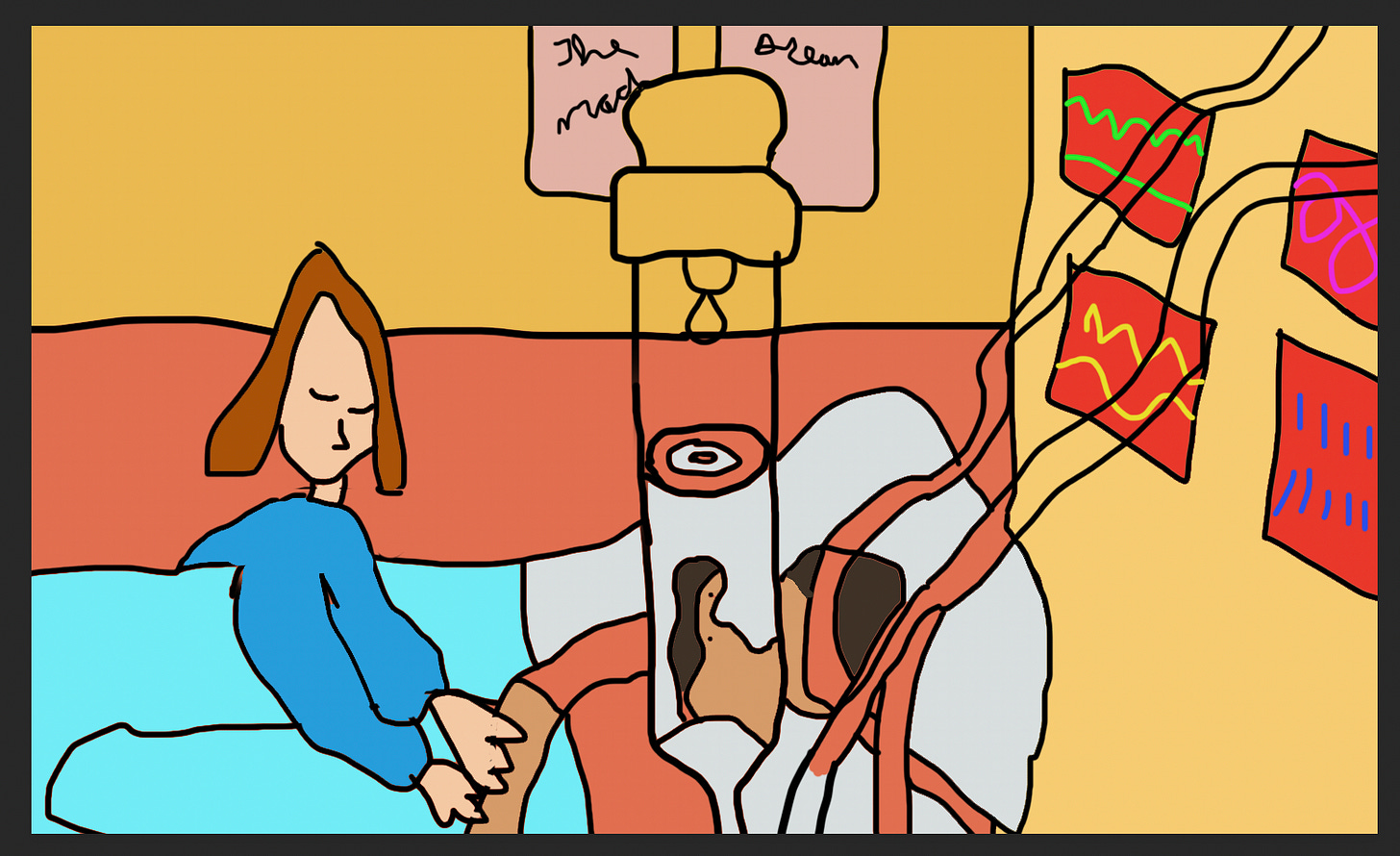

I saw this music video she made and knew that there was no one else in the world I’d rather work with on The Dream Machine. Her style was so sensual, so designed, and I couldn’t get enough of the way her worlds ate themselves. The frames she made felt dynamic and alive. In short, in Frances’ work, I felt very much that artifice came first, and I felt a deep aesthetic kinship with her immediately.

Over the course of that summer, Frances began imagining the world, sketching out the characters, and creating a color palette.

Then she began sending me images of things in motion, like this original version of The Dream Machine.

My skin was a goosebumps farm. The possibilities of animation clarified in my imagination, and this world that vexed me my entire adult life all of a sudden became possible.

Every week I would meet Frances on Wednesday at 3pm, morning her time in New Zealand, and she would share with me her progress of the week. Second by second, week by week, I watched the world turn from idea into reality.

When I began working with Frances, the idea was we’d take the remainder of 2022 to finish the film. However, the deadline came and went. This initially made me uneasy as I’m one to love checking a box, finishing a project, and moving on with my life. But Frances assured me: We need to make this as good as possible, which is going to slow us down.

I, up until this moment, have refused to slow down. But I couldn’t betray this collaborator, and so I followed her lead and took the path she wanted to take. And so we spent 2023 continuing to check in with each other once a week, 3 pm on the dot, and going over all the new clips that had been created.

It’s difficult to describe wanting to watch something be real for so long, finally becoming real. In the span of having the idea/writing the script to this project being fully realized, drawn, voiced, and scored, I had lived so many iterations of my life. I had loved, I had lost, I had raised a human. But this idea was a constant through it all, and now, by March 2024, here had finally arrived on Earth and was right in front of me.

Late in November 2024, the night we got our invitation to screen The Dream Machine at SXSW, my best friend Billie and I drank champagne, but not before I absolutely bawled my eyes out for the entire journey of this movie. It was like a deluge of grief from all my lives lived: Moving from Paris to LA, the version of the short film I was never able to make, the version of the movie I started making when Jesse was alive, the final version she never got to see, and the good news I never got to share with her.

I look forward to making so much beauty for the rest of my life. It’s all I want to do with my days. This short will always be the first thing I ever made that I thought was really truly beautiful. I knew it when I was 23, and I knew it when I was 39.

![Guy Maddin – [FILMGRAB] Guy Maddin – [FILMGRAB]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xlql!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcedc1ba5-137b-4357-9f23-aa879e9e7cc9_853x480.jpeg)

Oh! Jimmy! I had no idea! The story of DM's evolution blows me away! When I first saw DM, i knew you'd created a phenomenal piece of art. I do see two kindred spirits in this collaboration. What a loving, gorgeous, culmination of persistence, loss and even serendipity.

Congtatulations. Sending boatloads of love and admiration!

PS.

I love your characterization of Matisse's work. I certainly do see it in Frances's work too. I'm channeling what I think of as a Matisse affect/effect myself as I begin trying to create in 2026. Certainly not so sophisticated as your articulation of artifice as a bulwark ? against propaganda. But maybe that's why he's so inspiring to me right now.

Great words